Youth Athlete Development and Growth-Related Injuries

If you’ve ever watched a 13-year-old hobble off a football pitch clutching their knee, or seen a young gymnast wince every time she lands a jump, you already have some sense of what this article is about. Youth sport is brilliant, and the benefits of getting kids active early are well-documented. But there’s a side to it that doesn’t get nearly enough attention: the fact that a growing body is genuinely vulnerable in ways that an adult body simply isn’t. Bones are still forming, tendons are under tension from rapid growth spurts, and the whole system is in a state of constant flux. Understanding that is the first step to keeping young athletes healthy and on the field for the long haul.

Physiology of the Growing Athlete

The most important thing to understand about young athletes is that they are not small adults. Their skeletons are still developing, which means there are areas of soft, cartilaginous tissue, called growth plates or physes, at the ends of the long bones. These areas are responsible for bone lengthening, but they’re also significantly weaker than mature bone. Forces that an adult skeleton absorbs without any trouble can cause real damage at a growth plate in a child or adolescent.

Then there’s the growth spurt itself. During Peak Height Velocity (PHV), the period when a young person is growing fastest, bones can lengthen faster than the surrounding muscles and tendons can adapt. This creates tightness, reduced flexibility, and altered movement patterns, all of which increase injury risk. A teenager who had beautifully coordinated movement at 11 might suddenly look awkward and stiff at 13, not because they’ve stopped training, but because their skeleton has temporarily outpaced everything else. This is normal, but it does require careful management.

Skeletally immature athletes also tend to have different injury patterns compared to adults. Where a grown man might rupture a ligament under heavy load, a child doing the same movement is more likely to sustain a bony injury at the growth plate. The ligament, paradoxically, can actually be stronger than the bone it attaches to during this stage of development.

Common Growth-Related Injuries

Apophyseal injuries (traction apophysitis)

Apophyses are bony prominences where tendons attach to bone. During adolescence, these sites are still partly cartilaginous and are therefore vulnerable to repetitive traction stress. The result is a group of conditions called traction apophysitis, and they’re remarkably common in active young people.

Osgood-Schlatter disease is probably the most well-known of these. It affects the tibial tuberosity, the bony bump just below the kneecap where the patella tendon inserts. During running, jumping, and kicking, the quadriceps muscle pulls repeatedly on this site. In a skeletally immature athlete, this can cause pain, swelling, and a visible lump. It’s particularly prevalent in sport-heavy adolescents aged 10 to 15, and while it tends to resolve once growth is complete, it can significantly disrupt training in the meantime.

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome is similar but affects the inferior pole of the patella rather than the tibial tuberosity. Sever’s disease, meanwhile, targets the calcaneal apophysis at the heel, where the Achilles tendon inserts. It’s one of the most common causes of heel pain in children between 8 and 14, especially those who play high-impact sports on hard surfaces.

Physeal injuries

Physeal injuries, or growth plate fractures, are classified using the Salter-Harris system, which categorises the fracture by its relationship to the growth plate, the metaphysis, and the epiphysis. Some types heal well with conservative management, while others carry a risk of growth disturbance if not handled properly. This is one of the reasons it’s so important that young athletes are assessed by clinicians experienced with this age group rather than simply applying adult injury protocols.

Early sport specialisation, where a child commits to a single sport year-round from a young age, is increasingly linked to overloading specific physeal sites. The repetitive, one-directional stress on bones that haven’t finished developing is a recipe for trouble.

Overuse injuries

Beyond the growth-specific conditions, young athletes are also susceptible to overuse injuries more broadly. Stress fractures can develop when repetitive loading outpaces the bone’s ability to remodel. Little League elbow and Little League shoulder, conditions affecting the medial elbow and proximal humeral physis respectively, are classic examples of what happens when young throwing athletes do too much, too soon. Hip apophyseal avulsion fractures, where a forceful muscle contraction actually tears away a piece of bone at the apophysis, are also seen in sprinters and kickers whose musculotendinous units are under significant tension during growth.

Risk Factors

Not every young athlete will develop these conditions, and understanding the risk factors helps coaches, parents, and clinicians spot who needs closer attention. Intrinsic factors include things the athlete brings with them: rapid growth rate, muscle-tendon imbalance (where bones have grown faster than soft tissues), joint hypermobility, and previous injury history. Some kids are also simply built in ways that place more stress on certain structures during particular movements.

Extrinsic factors are where the sporting environment comes in. A sudden spike in training volume, too little rest between sessions, hard training surfaces, poor footwear, and early specialisation all contribute meaningfully to injury risk. The sport itself matters too. Gymnastics places enormous demands on the spine and upper limbs in young athletes. Football involves repeated high-speed running, cutting, and kicking. Swimming, while generally lower-impact, can still overload the shoulder in high-volume programmes. None of these sports are inherently dangerous, but each has its specific patterns of risk that need to be understood and managed.

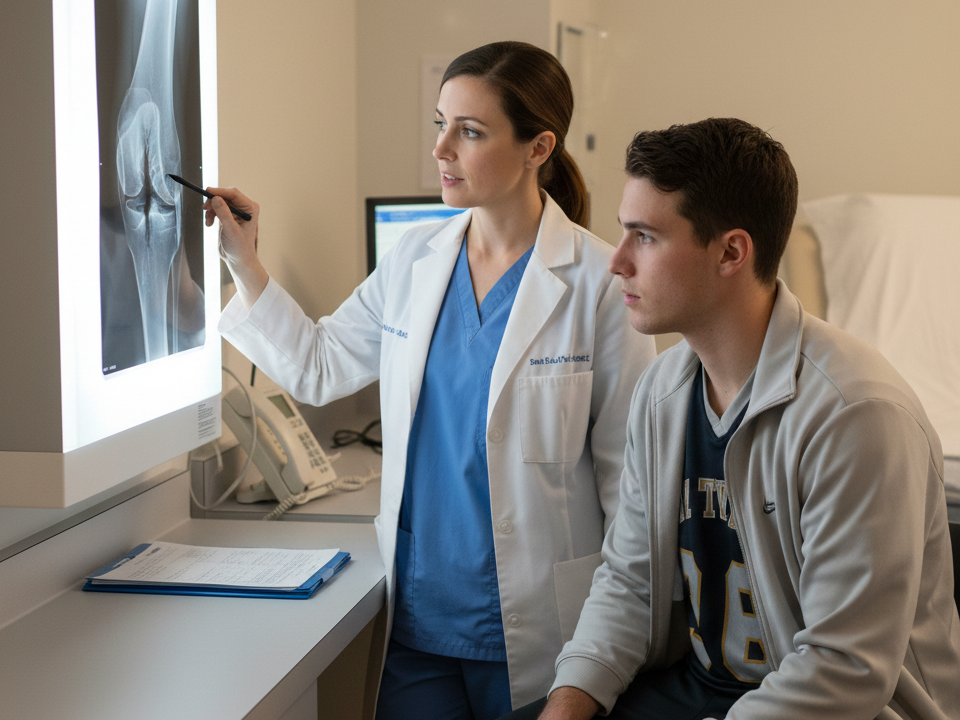

Assessment and Diagnosis

Assessing a young athlete is a different proposition to assessing an adult. Clinical presentation can be subtler, children often struggle to describe symptoms precisely, and the differential diagnosis includes conditions that are specific to this age group. A thorough assessment needs to consider the athlete’s stage of growth, their sport and training load, and the location and behaviour of their pain.

Imaging can be useful but comes with caveats. X-rays are often the first-line investigation for suspected physeal injuries or apophysitis, but growth plates naturally appear as gaps on X-ray and can be mistaken for fractures by clinicians unfamiliar with paediatric imaging. MRI offers better soft tissue detail and can identify bone oedema early, while ultrasound is increasingly used to assess apophyseal sites dynamically. None of these tools replace a careful clinical history and examination.

One of the most valuable things a physiotherapist can do at this stage is screen for growth-related issues before they become injuries. At Applied Motion, practitioners working with young athletes take a developmental approach to assessment, considering not just where it hurts but where the athlete is in their growth trajectory and what stresses their sport is placing on their body. Catching a problem at the irritation stage is far preferable to managing it once it’s become a full-blown injury.

Physiotherapy Management

The cornerstone of managing growth-related injuries is load management. That typically means reducing the provocative activity, whether that’s a temporary reduction in training volume, a modification of the specific movement causing irritation, or a short period of relative rest. “Relative” is the key word here. Complete inactivity is rarely necessary or helpful, and keeping young athletes engaged with some form of movement is important for both physical and psychological reasons.

Flexibility work is central to rehab for conditions like apophysitis, where muscle-tendon tightness is a driving factor. Regular stretching of the quadriceps and hip flexors, for instance, can meaningfully reduce the traction stress on the tibial tuberosity in Osgood-Schlatter cases. Strengthening, particularly through eccentric and isometric loading, is increasingly supported by evidence for tendon and apophyseal conditions. Programmes like the Spanish squat or wall sit variations for patellar tendon issues have shown good results in this population.

Pain management in young athletes needs to be handled thoughtfully. Anti-inflammatory medications may have a role in the short term, but the goal of physiotherapy is to address the underlying load-tissue capacity imbalance, not simply to suppress symptoms. Return-to-sport decisions should be based on functional criteria, including strength benchmarks, movement quality, and symptom response to progressive loading, rather than time alone.

Prevention Strategies

Prevention is a word that gets thrown around a lot in sports medicine, but in youth athletics it genuinely matters. The Long-Term Athlete Development (LTAD) framework provides a structured approach to planning training across the different stages of a young person’s growth, emphasising age-appropriate loading, skill development, and recovery. It’s not a rigid prescirption, but it offers a sensible framework for coaches and parents trying to balance development with safety.

Monitoring training load in young athletes is more art than science at present, but simple tools like session RPE (rate of perceived exertion) and acute-to-chronic workload ratios can help coaches spot when an athlete is accumulating more fatigue than their body can handle. The goal is consistency over intensity, particularly in the 12 to 15 age range when growth spurts are most likely.

Perhaps the single most effective thing a sporting environment can do for young athletes is resist the pull toward early specialisation. Research consistently shows that athletes who sample multiple sports during childhood and adolescence tend to have longer, healthier careers than those who specialise in one sport before the age of 14. They develop broader movement literacy, experience less repetitive tissue loading, and are often more resilient when they eventually do specialise. Encouraging kids to play different sports across different seasons isn’t holding them back; it’s building a more durable athlete.

Education is a big part of this too. Coaches who understand growth-related injury patterns can adjust sessions accordingly. Parents who know what Sever’s disease looks like don’t panic or push through symptoms unnecessarily. Young athletes who understand why they’re being asked to modify their training are more likely to follow through with it.

Psychosocial Considerations

Sport is often deeply wrapped up in identity for young people, and injury can knock that in ways that go well beyond the physical. A 14-year-old who defines herself as a swimmer and is suddenly told she needs six weeks out of the water isn’t experiencing an inconvenience; she may be experiencing something closer to a small identity crisis. This is worth taking seriously.

Physiotherapists working with this age group need to be attentive to how young athletes are responding emotionally to injury and enforced rest. Signs of frustration, withdrawal, or anxiety about returning to sport are common and worth addressing directly. Keeping the athlete involved in team environments where possible, setting clear and achievable rehabilitation goals, and making sure they understand the purpose of each stage of recovery all help maintain engagement and motivation.

Managing the expectations of parents and coaches is equally important. Well-meaning adults can sometimes pressure young athletes to return before they’re ready, particularly in competitive environments or when selections are coming up. Part of the clinician’s role is to advocate clearly for what the athlete’s body actually needs, even when that’s not what everyone around them wants to hear.

Keeping Young Athletes in the Game

Growth-related injuries are a predictable, manageable part of youth sport. They don’t have to mean long absences, derailed seasons, or lasting damage. With the right knowledge, appropriate load management, and timely physiotherapy input, most young athletes come through these conditions well and go on to have long, healthy sporting careers.

The key is treating young athletes as the distinct population they are, not scaled-down adults, but people in the middle of a genuinely complex developmental process. Their bodies are doing something remarkable. The job of everyone around them, coaches, parents, physios, and the athletes themselves, is to support that process rather than push against it.

If you’re concerned about a young athlete in your care, or want guidance on load management and injury prevention for developing players, the team at Applied Motion has extensive experience working with this age group and can provide assessments tailored to where an athlete is in their growth and development.